It hasn't happened yet, anyway. The 25th anniversary of the New York Nets' first American Basketball Association championship passed recently with no fanfare and hardly any notice. The ABA is mostly a flickering memory -- rekindled lately as the San Antonio Spurs and Indiana Pacers, two of its four surviving franchises, kept rolling through the NBA playoffs. There is hardly a thought of the night in May 1974 when the Nets finished off the Utah Stars and when Nassau Coliseum looked as if it were going to be a basketball hub for years to come.

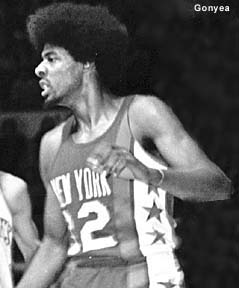

"One thing that's a pet peeve or whatever is just the seeming insignificance of it to the whole basketball world, which keeps trying to sweep it under the rug as if it never happened," said Julius Erving (right), the main reason the Nets won that title and another in 1976. But his statistics from his ABA years aren't included in the totals listed by the NBA. "Discussions come up regarding my career, and people say, 'An 11-year pro ball career,' as if the ABA never happened. It was a constant uphill struggle."

"One thing that's a pet peeve or whatever is just the seeming insignificance of it to the whole basketball world, which keeps trying to sweep it under the rug as if it never happened," said Julius Erving (right), the main reason the Nets won that title and another in 1976. But his statistics from his ABA years aren't included in the totals listed by the NBA. "Discussions come up regarding my career, and people say, 'An 11-year pro ball career,' as if the ABA never happened. It was a constant uphill struggle."

There is only one thing more he can say about it now: "I wouldn't trade it for anything in the world."

Nor would anyone else from the team that reached the top of its hill a quarter-century ago. There was no tarnish on the players in the league with a red-white-and-blue ball then, and there is none now, at the silver anniversary. To them, it was and is sheer gold. "Twenty-five years, huh?" said Erving, now executive vice president of the Orlando Magic. "We should be drumming something up."

It has been 25 years since newspapers speculated that the Nets -- led by the 24-year-old Dr. J -- could be New York's next sports dynasty. Twenty-five years since then-second-year guard Brian Taylor said, "This is only our first championship, but it's not going to be our last."

"It was probably the crucial part of my early life," Taylor said recently. Now a father of five and an administrator / girls basketball coach at the prominent Harvard-Westlake prep school in Los Angeles, he reflected and added: "I was able to stay in the New York area and I had so much fun. I had great friendships, especially with Julius. I looked up to him as a big brother."

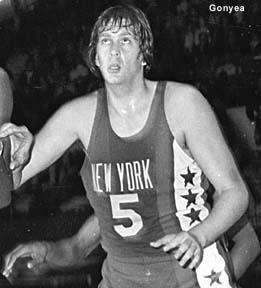

"We were really strong at forward, really strong at guard. We could hold our own with anybody. I remember we were always fighting with the Knicks for recognition," said Billy Paultz, then the center, now a Florida-based vice president for Minuteman Press International. "It was an exciting time for Long Island."

"If the ABA were playing today with cable TV and all the exposure, it would have really taken off," said Kevin Loughery, the coach of those Nets, now in retirement except for some commentary for ESPN Radio. "That was a very good team. If we had been able to go into the NBA with that team, we could have been formidable."

People who were around the Nets then remember the excitement of acquiring Erving the previous summer from the Virginia Squires, who couldn't afford him and feared he would jump to the NBA. Others recalled what a good complement rookie forward Larry Kenon was. They remembered the three-hour tongue-lashing they got from Loughery and assistant coach Rod Thorn after an early-season eight-game losing streak, and how the team turned around after the coaches stopped using fullcourt pressure the whole game and decided to start rookie John Williamson at guard in place of John Roche.

They remembered the late-season trade of Roche for Mike Gale and Wendell Ladner, and how the latter would crash into scorer's tables. "He was the X factor," Erving said. There was the stunning semifinal sweep of the Kentucky Colonels and Artis Gilmore. "The Whopper was the one that series," Erving said, using Paultz' nickname. Said Paultz (at left): "I was fortunate enough to play Artis a lot of times during the year. That gave me an advantage. I was never going to stop him; the thing was, he wasn't able to dominate the series."

They remembered the late-season trade of Roche for Mike Gale and Wendell Ladner, and how the latter would crash into scorer's tables. "He was the X factor," Erving said. There was the stunning semifinal sweep of the Kentucky Colonels and Artis Gilmore. "The Whopper was the one that series," Erving said, using Paultz' nickname. Said Paultz (at left): "I was fortunate enough to play Artis a lot of times during the year. That gave me an advantage. I was never going to stop him; the thing was, he wasn't able to dominate the series."

The Nets recalled the final series. "The first thing I think about is my teeth -- I got my teeth knocked out by Ron Boone," Taylor said, laughing as he recounted the price for aggressive defense.

"We thought we were going to win it in Utah, so I had to buy all this champagne," said trainer / travel secretary Fritz Massmann, retired from the Nets and still living in Babylon. But the Nets lost Game 4 of the final series. "I had to pack it all up and bring it back to Nassau."

Mostly, they remember Erving. "He was un-be-lievable," said Thorn, now senior vice president of the NBA. "Kevin and I would sit on the bench and say, 'I can't believe he just did that.' " Thorn said that being part of that championship helped him get a head coaching job with the Spirits of St. Louis and the general manager's job with the Chicago Bulls, which led to his current position.

Erving said that title opened doors for him, too. "It was a pretty good launching pad in terms of Julius Erving-as-spokesman and endorser and ambassador and future Hall of Famer," he said. "Being pivotal in a team's success gave me the opportunity to challenge the media and the world of sports to see if I could measure up. I think I measured up."

But the Nets never did attract huge crowds or generate a lot of passion. Also, they were knocked out of the playoffs by St. Louis in 1975, which prompted the club to trade Kenon, Paultz and Gale to San Antonio for Swen Nater, Rich Jones and Chuck Terry.

The Nets won again in 1976, mostly because of Erving. "That was as good a brand of basketball as anyone has ever played," said Loughery, who later coached Michael Jordan. "I don't think the true Doc was ever seen in the NBA."

The true New York Nets sure weren't. When four ABA teams were absorbed into the NBA in 1976, owner Roy Boe had to pay so much in league fees and indemnities to the Knicks that he couldn't afford to give Erving the raise for which he was holding out. Erving was sold to the Philadelphia 76ers, and by the fall of 1977, the team was in New Jersey (and still hasn't recovered its glory).

"Professionally speaking, I don't think there ever was a total sense of proprietorship between the Nets and the whole Island," said Erving, a Long Islander from Roosevelt. "We'd get those eight- or nine-thousand consistently, but it wasn't as though it was Long Island's team. Long Island never embraced the Nets the way it should have."

There were no Long Island tributes to Erving and his teammates this month, no poignant salutes to Williamson, who died of kidney failure in 1996, and Ladner, who died in a 1975 plane crash. The sporting public never did grasp how good their league was. "We never really knew ourselves, until the leagues merged," said Taylor, who averaged 17 points for the NBA's Kansas City Kings in 1976-77 (second on the team to Boone). "We realized we were good, talented and fast." By then, it was too late to help the champion Nets. "If you ask me," Massmann said, "the ABA was the league that should have survived."

The final steal in the Nets' first American Basketball Association championship game 25 years ago never showed up in the boxscore. It was performed by the ballboy, Al Trautwig (left). "There was a timeout with six seconds left and the team broke from the huddle. There were a lot of fans around the court," said Trautwig, now a broadcaster for MSG Network. "I wanted to get that ball. That was my job." He wanted to make sure no fan made off with it, that is. So when Billy Paultz made a long toss downcourt, Trautwig bolted onto the court, five feet inside the baseline, jumped and caught it. "Then I heard a scream from behind me. It was Larry Kenon. He obviously wanted to end the game with a big dunk," Trautwig said of the Nets forward. "Norm Drucker was the ref. He told me, 'I should give you a technical, but I think Larry is going to take care of this.' " Kenon at least gave Trautwig a very dirty look, and Trautwig remembers Kenon being very unhappy with him. And they did play the final six seconds in the Nets' 111-100 win over the Utah Stars. To this day, Trautwig doesn't know who got the basketball that night. He does feel a debt to the Nets executives who gave him a job in 1969, when he was in high school and the team moved into the Island Garden in West Hempstead. "I could see the Island Garden from my house," he said, adding that he made a dollar per game at first. The enterprise turned out to be a lot more lucrative. "Being a ballboy led me to being on the radio and started my whole career," he said. It also got him a job as a stickboy for the Islanders, which ultimately gave him a shot on the USA Network's hockey coverage, which led to all kinds of other chances. "It really affected what I did for the rest of my life." The final steal in the Nets' first American Basketball Association championship game 25 years ago never showed up in the boxscore. It was performed by the ballboy, Al Trautwig (left). "There was a timeout with six seconds left and the team broke from the huddle. There were a lot of fans around the court," said Trautwig, now a broadcaster for MSG Network. "I wanted to get that ball. That was my job." He wanted to make sure no fan made off with it, that is. So when Billy Paultz made a long toss downcourt, Trautwig bolted onto the court, five feet inside the baseline, jumped and caught it. "Then I heard a scream from behind me. It was Larry Kenon. He obviously wanted to end the game with a big dunk," Trautwig said of the Nets forward. "Norm Drucker was the ref. He told me, 'I should give you a technical, but I think Larry is going to take care of this.' " Kenon at least gave Trautwig a very dirty look, and Trautwig remembers Kenon being very unhappy with him. And they did play the final six seconds in the Nets' 111-100 win over the Utah Stars. To this day, Trautwig doesn't know who got the basketball that night. He does feel a debt to the Nets executives who gave him a job in 1969, when he was in high school and the team moved into the Island Garden in West Hempstead. "I could see the Island Garden from my house," he said, adding that he made a dollar per game at first. The enterprise turned out to be a lot more lucrative. "Being a ballboy led me to being on the radio and started my whole career," he said. It also got him a job as a stickboy for the Islanders, which ultimately gave him a shot on the USA Network's hockey coverage, which led to all kinds of other chances. "It really affected what I did for the rest of my life." |